My dad started his adult life in the1940’s hand-milking a herd of Jersey cows on a farm without electricity in Northwestern Illinois, where mice jumped out of the cereal boxes in the morning. He’d come from a hard home life, and eventually worked his way out of poverty to become a banker, a small-town patriot, and community leader. Like most parents, he hoped that I would have a better life. He felt that I had the skills to be a good lawyer. He saw that the lawyers in his little town had intelligence, that they had respect, and that they had enough fire in their hands not to be pushed around like the ‘little guy’ he once was.

When I graduated from law school and passed my first bar exam, dad presented me with a little silver bowl (ok, it was only silver plated—money is not spent easily on luxuries in a life where savings were once a stack of quarters). But that little bowl had our shared last name engraved on it, followed by the letters ESQ, the date of my graduation from law school, and the date I passed the bar.

I didn’t see it all as that big of a deal. I was only one of many thousands of kids coming out of law school that year, and nowhere near the top of that heap, (at least by the east-coast standards of my law school). But I had reached a level to which Dad aspired, but could not achieve himself. I was a licensed professional. I’d found a good job. I had a future where I showered before work instead of after work like those that make a living with their hands do. I had become somebody, at least in his eyes. Those of you who are parents realize how many dangers, toils, and snares must be overcome to get your kids just this far.

As lawyers, we are salmon swimming upstream. As a group, have swum so hard that we have reached the apex level of development to which our entire educational system points: The level of being an ‘expert’ and a conscientious professional. Most all of us are able to think for ourselves, which is a remarkable achievement. Many of us have reached an even further stage where we’ve realized that not everyone thinks like we do, and are OK with it. We are able to take another’s perspective and see both sides of an argument. We must do so in order to function as lawyers and do what we do.

At each of these steps we left a substantial portion of the population behind who were unable to clear these hurdles. We are in fact an elite group.

The Distance Travelled.

I have immense respect for the distance we’ve travelled to reach our expert destination, and the vast amount of work done by our law schools and bar associations to maintain professionalism as our common floor. As lawyers:

- We enjoy a level of cognitive ability that allows us to metabolize complexity. We’re smart.

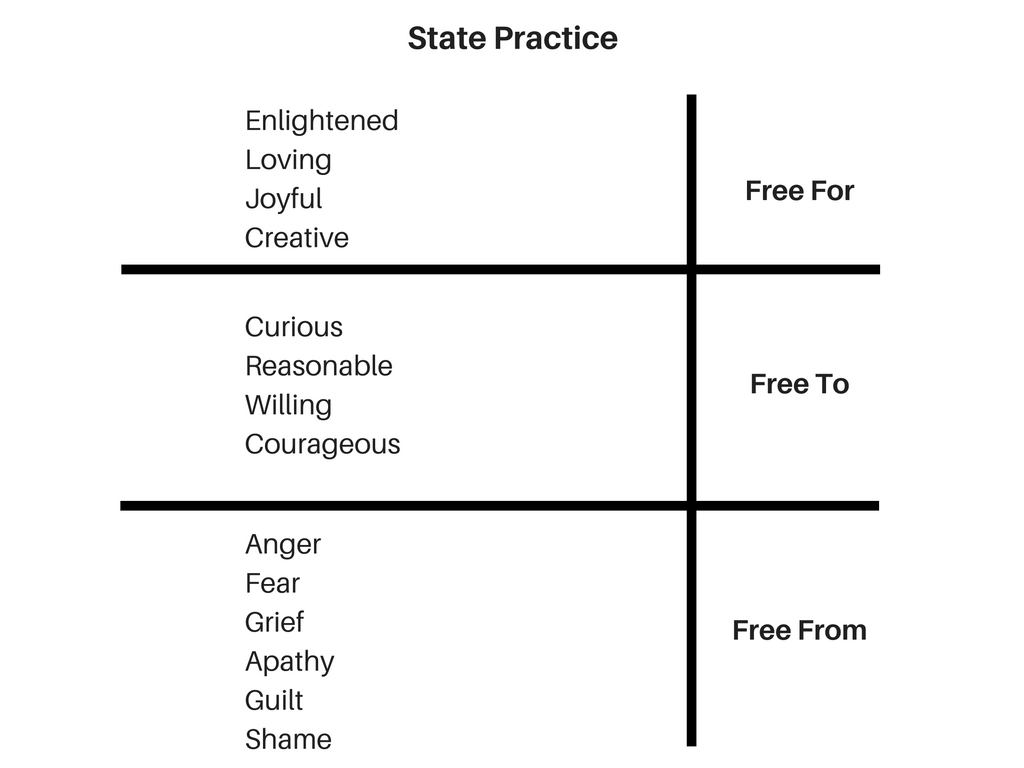

- Because of our training, we have the ability to default to reason as our base state. Reason is the capacity to access a state of being reasonable, instead of emotional and irrational, when the chips are down. A progression of states is shown in the figure below. Reason is a very high level of consciousness.

- Lawyers also have tremendous potential because we are working people. In the words of Khalil Gibran, “work is love made visible.” [1] This capacity for work distinguishes us.

The Invisible Ceiling.

So with all of this going for us, why are so many of us unhappy with our careers and the way life is turning out for us? My answer is this:

The level of ‘expert’ (and its ultimate embodiment as a conscientious professional) is nowhere near the end of adult human development. Not even close. Lawyers are a high potential group who require specific new challenges to continue to grow and further develop as both human beings and professionals.

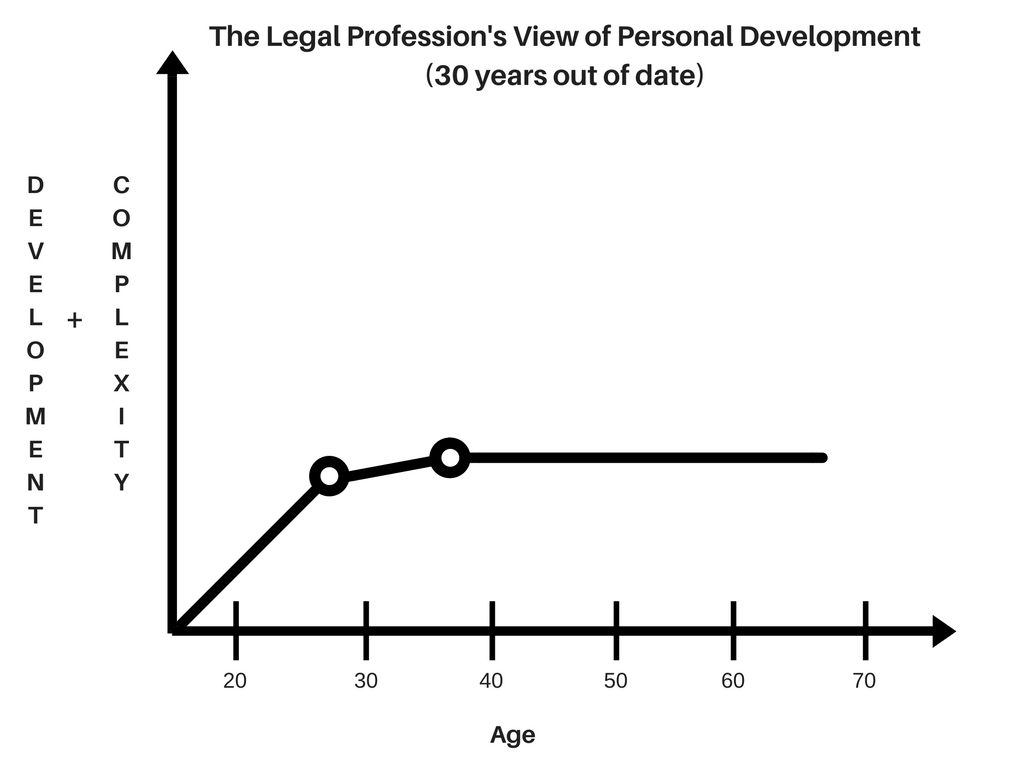

We are being denied these challenges by a mythology that is at least 30 years out of date.

The following graphic illustrates the life-view taught to us in law school, and reinforced by our current forms and practice of continuing education:

Our myth says that our growing up is mostly finished as we reach adulthood, find our professional calling, and learn how to do our work. That work is found to be so meaningful and fulfilling that the subsequent tens of thousands of hours of it, (with a little vacation, self care, and family life on the side), is all that we will ever need for a successful life. For a happy minority of us, this is a reality. For the vast majority of us, however, it’s just not true.

We don’t have enough air to breathe because the developmental glass ceiling (represented by the flatline in the figure above) is preventing us from leaning into natural and progressive levels of adult development that sentient beings of our intelligence and potential simply require to stay fully in the game. This static situation presents a real danger to us. It’s the root cause of our burnout, boredom, sense of meaninglessness, and dissatisfaction.

All of us, without exception, will find ourselves interacting with this ceiling at some point in our careers. We find that we are longing to move forward but the legal culture that we are within is not moving forward. We find ourselves within a culture that is just producing the same year of experience over and over again, even as we long for more. And our choices are stark. Either learn to like it, leave, or find a way to get a life on the side. We’re left to do this pretty much all on our own.

The Next Step—The Self-Authoring Life.

Fortunately, there’s a better way. This better way is to evolve out of our current situation, using what we’ve already achieved as a foundation. It’s time to use what we’ve achieved as a springboard to something even better.

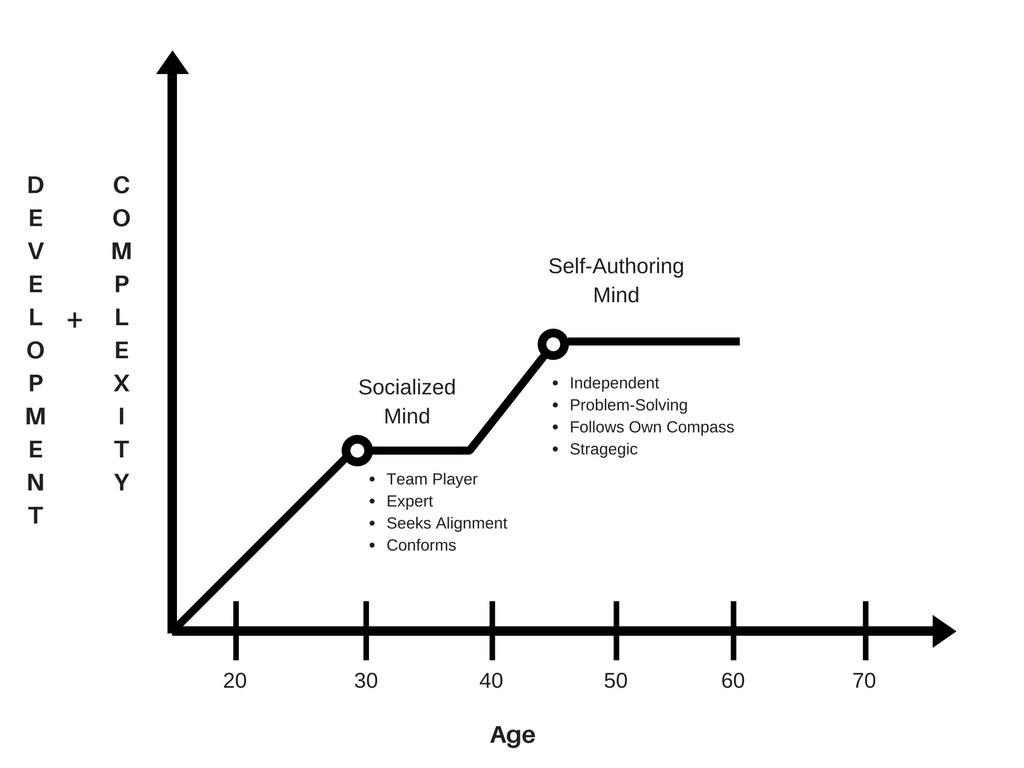

The Flatline depicted above will change to look like this:

The next stage beyond ‘expert’ is the self-authoring stage.

In my work as a mediator, it’s been my privilege to watch about 10,000 lawyers in action over the years, and I can say unequivocally that every lawyer I’ve ever met who has a 7 figure income also has a self-authoring mind. This is 100% of the folks observed, without exception.

Here’s what the self-authoring types have in common:

- They are often not the top students in law school, though some of them are. A study of Harvard grads found no correlation whatsoever between grades in law school and later financial success. [2] Top students are good at doing assignments given to them by others. These folks are good at doing assignments they have given themselves.

- They think strategically, and everything they do is part of a long term strategy. They think in 3-5 year time blocks, with eighteen months as close-in range.

- This long-term strategy is fueled by a powerful, emotionally-fueled present-sense vision of who they might become, which they see as something that has already happened and they are simply uncovering a step at a time. Law can and is used as sub-part of this strategy, but it is seen as a means to an end, not an end in itself.

- They are far more interested in relationships than other working lawyers. What they know is often not as important as who they know.

- They treat themselves like precious objects, and get the support they need without hesitation, They invest in themselves, and have coaches to support them in their lines of development, whether this is cognitive, physical, or relational.

- They run and own businesses, and see themselves as running their own business from day one, even if they are employees. If they are in a law firm, they are using the firm as part of their strategy, even as the firm is using them. To a person, they do not have an ‘employee mentality.’

- They have a strong interest in teamwork, and want to create high-functioning teams so that they can create more and get more done. (Expert level lawyers do not do this. Instead, experts function in a kind of ‘parallel play’ where they do what they do, others do what they do, and the relational space between them is oddly thin). One of the main reasons self-authoring people go to work is to bond with a team of other creators. If the job does not generate this environment, self-authoring people will consider themselves underpaid.

- They see the people, circumstances, judges, opposing lawyers, clients and staff as pieces on their chessboard, and have a clear idea of what winning looks like.

- They develop and spend time in peer-to-peer learning organizations that share knowledge.

- They have the idea that other people should be working for them, not the other way around.

- Many of these self-authoring lawyers will see the law as a stepping stone into business, or other activities within the law where they can leverage their time and stop working by the hour.

I hope you can see by now the difference between this and the ‘expert mind’ that most lawyers inhabit. Relationships. Teams. Strategic Vision. Definite Plans. Commitments to Yourself. These are the themes of the self-authoring stage. This all can be done quite ethically within the rules for lawyering, and often these folks set standards of practice that other people emulate.

Once you see ‘expert’ as a lesser-included stage, all the work you’ve done to get there falls into the same category as getting dressed, feeding yourself, driving to work, and reading the paper, which are complex skills that are just assumed as part of the job you are doing now.

It’s helpful to see beyond where we are now. By aiming higher, we can shoot through the target that we now see as apex, and become even better lawyers as a result.

The movement into the self-authoring stage is already happening with the best in our profession. [3] I hope that you can find your way into it, and get the help you need to live a larger and more fulfilling life within the context of our profession.

Regards,

Ross

[1] Khalil Gibran, The Prophet. Alfred A. Knopf (September 23, 1923).

Here are some of my favorite lines from a section of this great spiritual classic on work:

You work that you may keep pace with the earth and the soul of the earth.

For to be idle is to become a stranger unto the seasons,

and to step out of life’s procession, that marches in majesty and proud submission towards the infinite.

When you work you are a flute through whose heart the whispering of the hours turns to music.

Which of you would be a reed, dumb and silent, when all else sings together in unison?

Always you have been told that work is a curse and labour a misfortune.

But I say to you that when you work you fulfill a part of earth’s furthest dream, assigned to you when that dream was born,

And in keeping yourself with labour you are in truth loving life,

And to love life through labour is to be intimate with life’s inmost secret.

Work is love made visible.

And if you cannot work with love but only with distaste, it is better that you should leave your work and sit at the gate of the temple and take alms of those who work with joy.

For if you bake bread with indifference, you bake a bitter bread that feeds but half man’s hunger.

And if you grudge the crushing of the grapes, your grudge distils a poison in the wine.

And if you sing though as angels, and love not the singing, you muffle man’s ears to the voices of the day and the voices of the night.

[2] The Men and Women of Harvard Law School: Preliminary Results from the HLS Career Study, published by the Harvard law School Center of the Legal Profession, 2015.

[3] About a quarter of the men that graduate Harvard law school don’t practice law—they have moved into much better and higher paying careers.

The Harvard Study, page 25,47.

Leave a Reply